Who Signed the Pinker Letter?

July 22, 2020

I hate feeling compelled to do this, but here we are. tl;dr: I ran some quick ‘n dirty stats on the signatories of “the Pinker Letter”, and it’s not “just graduate students.” But also: why are we doing this?

I won’t rehash the history of the Pinker letter. I assume if you’re reading this, you know what it is, and you know the controversy surrounding it.

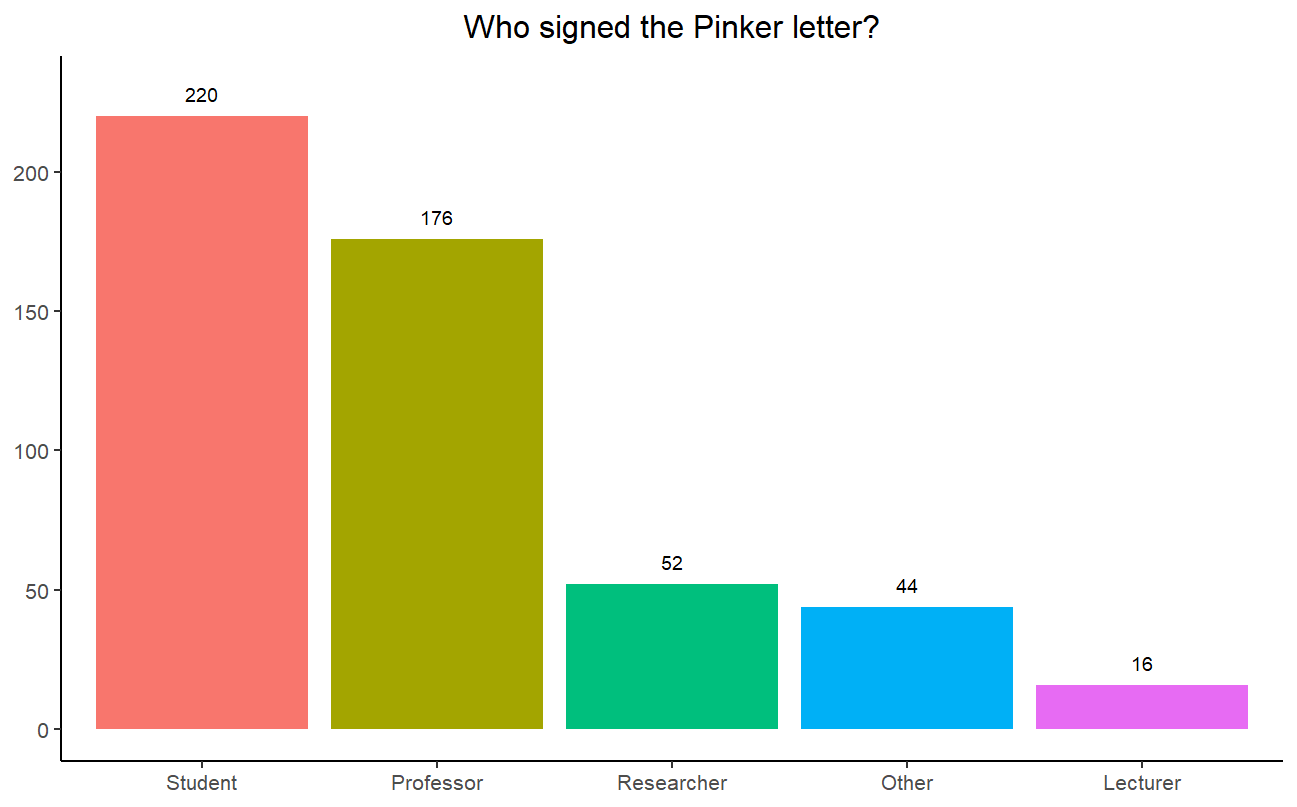

The point of this post is pure and simple. On several occasions, in apparent efforts to discredit “the Letter,” Steven Pinker has alluded to the academic status of its signatories. Most recently, on the BBC radio program “World at One” with Sarah Montague, he claimed, “Most of them were graduate students and lecturers… by no means an indication of the sentiment of professional linguists.”

I won’t go into the many ways in which I find that statement problematic. I defer to my colleagues for that one (here’s a recent example from Dr. Caitlin Green).

What I want to point out here is that this statement is, to give the benefit of the doubt, an oversimplification. At worst, misleading or disingenuous. As other linguists have pointed out, 7 LSA Fellows figure among the signatories of the Letter, and there are definitely professors to be found on the list.

So let’s quantify who signed the Letter, to put this to rest once and for all. With reproducible R code (see the very end of the post)! This is a very simple task. The data were imported from a local CSV file as sign.

I then generated a list of all unique text in the “Role” column and manually classified them as either professor, student, lecturer, researcher or other. I hope I didn’t step on any toes with this one. I looked up a couple of ambiguous titles, but most I went with what was written. Again, you can see these categories in the code. Some particularities:

- Visiting professors were counted as professors.

- Postdoctoral researchers were grouped in with data scientists and so on, unless “teaching” was indicated (in which case, they were counted as a lecturer)

- Alums were counted as students if nothing else was indicated.

- “Other” includes professionals within and outside of linguistics.

- Anyone listing “lecturer” status in the UK, South Korea, Australia or New Zealand was manually changed to “professor,” as the title corresponds to Assistant Professor or higher in North America. (This affected 16 peoples’ classification.) Lecturers at European institutions were left off this list out of an abundance of caution.

Note that this exercise felt pretty weird to me. Academic rank is a strange thing, and this whole classification scheme felt a little unsavory and demeaning. Anyway. Once those roles are defined, we make a lookup dataframe and match people with their generalized roles. (I reordered the factor to make the bar graph pretty.)

Let’s take a look at the values:

- Student: 220

- Professor: 176

- Researcher: 52

- Lecturer: 16

- Other: 44

124 names lacked a title. These were excluded from the graph. If anyone wants to look them up, have fun.

Here are those results in a bar graph.

Take from this what you will. Don’t @ me.

I want to be crystal clear about one thing: even if the Letter was written exclusively by students, that shouldn’t discredit their claims a priori. A lot of Pinker defenders criticize the Letter and its proponents as levelling ad hominem attacks against Pinker – what is this, if not that? Pinker is using the identities of the Letter signatories as a tactic to invalidate its claims. Those claims should be addressed, rather than nitpicking or attacking an often arbitrary status. (Have you seen the academic job market??)

I’m going to stop there before I go off in a tangent. Again, this post is just to quantify who signed the letter, because some people think that matters.

I even hesitated to write this post for fear of giving credence to this kind of argument. But in the end, I wanted to show that, playing by these (harmful!) rules, dismissing the Letter based on the status of the people who signed it is not as easy as, ahem, certain people have made it out to be.

The code

sign = ### INSERT DATA HERE

other = c("NLP Engineer",

"Analytical Engineer",

"NLP Services",

"Alum",

"Private sector computational linguist",

"Faculty Librarian",

"Research Technician",

"Reader",

"Software Engineer",

"Education Developer",

"Alum, Linguistics Blogger",

"Speech Recognition Engineer",

"Co-host",

"Program Manager",

"Senior Linguist",

"Linguist",

"Computational Linguist",

"Executive Director",

"Director",

"Applied Scientist",

"Editor",

"Archivist, Linguist",

"Consulting Linguist and PhD alum",

"Speech-Language Pathologist and Linguistics graduate",

"Writer"

)

prof = c("Assistant Professor",

"Professor of Linguistics",

"Associate Professor",

"Professor",

"Adjunct Assistant Professor",

"Department chair",

"Associate Professor of Psychology",

"Affiliate Professor",

"Associate Professor of Linguistics",

"associate professor",

"Professor & Chair",

"Assistant professor",

"Fellow, Linguistics Society of America",

"Associate Prof.",

"professor",

"Professor & LSA Fellow",

"Term Assistant Professor",

"Professor and Chair, Department of Anthropology",

"University teacher",

"Emeritus Professor",

"Associate Professor Emeritus",

"Professor and Chair",

"Assoc Professor",

"Associate Research Professor",

"Assistant Professor of Linguistics",

"Associate Professor & Director of Undergraduate Studies Professor and Director of Graduate Studies",

"Professor and Director",

"Assistant Professor of Instruction",

"Presidential Professor",

"Associate professor",

"Professor Emeritus",

"Professor and Head",

"Visiting Assistant Professor, Linguistics"

)

lec = c("Lecturer",

"Instructor",

"Lector",

"Lecturer in Sociolinguistics",

"Director of Undergraduate Studies",

"Senior Lecturer",

"Senior lecturer",

"Sessional Lecturer",

"Visiting Instructor",

"course lecturer",

"Teaching Fellow",

"Postdoctoral Teaching Fellow"

)

stud = c("PhD student",

"Grad Student",

"PhD candidate",

"PhD Student",

"Graduate Student",

"PhD Candidate",

"graduate student",

"Student",

"PhD Researcher",

"Graduate student",

"Linguistics MA",

"Graduate Fellow",

"Ph.D Student",

"Phd. Candidate",

"PhD graduate",

"PhD Student NLP",

"President",

"TESL Student",

"PhD Student Computational Linguistics",

"Linguistics PhD",

"PhD. Candidate",

"MA student",

"MA Linguistics",

"Alumnus, MA Linguistic Theory and Typology",

"PhD Graduate",

"Undergraduate student",

"student",

"MA Linguistics graduate",

"Postgraduate Student",

"Alumna",

"Ph.D. Student",

"MA Student",

"Ph.D. student",

"PhD",

"PhD student/worker",

"MS Student",

"PhD student in Language Science",

"Co-presenter",

"PhD candidate, Communication",

"MA/PhD student",

"Ph.D. Candidate",

"Grad student",

"PhD Candidate, Linguistics",

"Undergraduate",

"Undergraduate Student",

"Alum, BA Linguistics + MS Theoretical Linguistics"

)

res = c("Postdoctoral Researcher",

"Postdoctoral Research Fellow",

"Postdoc",

"Researcher",

"Postdoctoral researcher",

"Research Fellow",

"Research Scientist",

"Postdoctoral Fellow",

"Visiting Research Fellow",

"Postdoctoral Associate",

"Postdoctoral Research Associate",

"Research Staff",

"Senior Research Scientist",

"Postdoctoral Scholar",

"Visiting Researcher",

"research staff",

"Data Scientist",

"Post-doc",

"Postbaccalaureate researcher",

"Independent Researcher and Consultant"

)

lookup = data.frame(

who = c(rep("Lecturer", length(lec)), rep("Other", length(other)), rep("Professor", length(prof)), rep("Researcher", length(res)), rep("Student", length(stud))),

role = c(lec,other,prof,res,stud)

)

sign$who = lookup$who[match(sign$V3, lookup$role)]

revise = c(111, 156, 161, 176, 290, 302, 304, 379, 334, 462, 444, 499, 524, 588, 617, 632)

sign[revise,]$who = "Professor"

sign = within(sign, who <- factor(who, levels=names(sort(table(who), decreasing=TRUE))))

library(ggplot2)

ggplot(sign[complete.cases(sign$who),], aes(x=who, fill=who)) +

geom_bar() +

geom_text(stat='count', aes(label=..count..), vjust=-1, size=5) +

theme_classic(base_size = 20) + theme(

axis.title = element_blank(),

legend.position = "none",

plot.title = element_text(hjust = 0.5)

) + scale_y_continuous(limits = c(0, length(which(sign$who=="Student"))+10)) + ggtitle("Who signed the Pinker letter?")