It's 'gif' and 'gif': The English lexicon goes both ways

31 août 2020

This post about the pronunciation of “gif” is written for a general public and uses International Phonetic Alphabet symbols rather than “hard” and “soft g”. Here’s all you need to know:

- Brackets [] indicate a phonetic transcription.

- [g] = the first sound of “good”. This is technically a velar stop.

- [dʒ] = the first sound of “Jerry”. This is technically a post-alveolar affricate. It’s different from [g] both in where and how it’s produced.

Let’s say you’re an English speaker, reading a text, and you run into a new word. Should you ever have to pronounce that word out loud, short of looking it up in a dictionary, you’ll draw on your knowledge of English – especially the correspondence between certain (combinations of) letters and the sounds they make. So far, so good, but sometimes there’s conflicting evidence in the lexicon. And while we like to think we all speak The Same English, in reality “your own personal English” is ever-so-different from someone else’s because your experiences with language are unique. Fortunately, this doesn’t usually keep us from understanding one another. For instance, when I moved to Canada and heard the first syllable of “pasta” being pronounced “pass” (and not with the vowel of “paw,” like I was used to), it was certainly new and notable for me, but it didn’t lead to any confusion. That difference you can easily pin down to regionality – you hear a certain pronunciation, and you can guess a thing or two about the person.

The “gif debate” strikes me as similar, but with a crucial distinction: I can’t think of any easy “group signalling” (intentional or otherwise) that either pronunciation brings with it, beyond simply the pronunciation itself. Saying it [dʒɪf] signals you’re a [dʒɪf]-er, pure and simple. You can’t tell where someone’s from, what socioeconomic class they might fit into, their sex or gender, etc., just from that initial consonant. If we could, I doubt we’d be talking about which form is “right” or “wrong”. Instead, we’d probably (imperfect beings that we are) fall into some pretty harmful traps if that distinction fell along some power differential. (Just look at “vocal fry.” Men use it more than women, but because it’s associated with women’s speech, it can seen as undesirable, unprofessional, and so on. As some have insightfully remarked, “Vocal fry is the new ‘shrill’.”)

With this post, I want to probe one aspect of why that initial, subconscious decision is made – when you first saw “gif”, why you heard it [gɪf] or [dʒɪf]. And to do that, we need to look at patterns and regularities in the English lexicon. I’m going to disappoint you right away: both forms can be justified, and because English speakers understand both of them, implicitly, both forms are “right.” The debate may be fun, but I think we all know deep down that nothing will ever definitively prove one over the other.

So what’s the evidence for each? Let’s start with the boring stuff…

Data (or is it “data”?)

The data come from the English Lexicon Project and consist of a text-based file of nearly 80,000 orthographic forms, their pronunciation and other information such as the number of syllables and frequency. “Frequency” should be read as the number of occurrences of a word in a given (very large) corpus. We’ll be using a log-transformed frequency, so keep in mind that what might look like small differences can in fact be very big.

The main processing starts by subsetting all words in English containing the sequence of letters “gi”. We then lemmatize them to weed out related forms (like “talk” and “talking”, etc.) and reduce them to a single, simple form. (Another, more complicated, manual process helps do this further. It removes a lot of adverbs and reduces pairs like “gilder” and “gilded”.) We then use Regular Expressions (think of these like a fancy “search and replace” that can generalize instead of performing only exact searches) to extract the phonetic transcription consonant and the vowel corresponding to these “gi” letter sequences. (At this stage, there’s no more room for ambiguity; if it returns “g” for the consonant, it means the [g] of “good”.)

We still need to get rid of some unfair forms that are overrepresented in the data. Not saying these offer no insight to our instincts – in fact, I think we should keep these in mind. However, they tend to obscure some more important trends. For instance, the present participle (“-ing” forms) of verbs ending in “ge” (like “arrange”) make up a lot of [dʒ] forms. Is this important to know? Yes! It means we encounter this mapping of “gi” to [dʒɪ] a lot inside words. Does it give us a deeper understanding of the number of unique forms in English corresponding to a certain consonant over the other? Not really. The same goes for all the “-ology” and “-ologist” forms, too.

What does that leave us with? 269 forms. Not a lot, but keep in mind that these are unique, simple forms. Now, let’s talk about competing evidence, starting with…

[g]-initialism

This is a term I’m pulling out of thin air. I think. But it means this: [g] has an advantage over [dʒ] at the beginning of words, both in number of forms and in their frequency. That is, there are more word-initial “gi” forms whose consonant corresponds to [g] (21) than to [dʒ] (15). Those [g]-initial words are also much more frequent (average log frequency of 6.03 vs. 5.17 for [dʒ]), thanks in large part to “give” and “girl”. (Want the raw frequency numbers? It’s 14198.57 vs. 2874.4! Thanks again to “give”.) “Giant” and “ginger” are the most common words in the [dʒ] camp. While “giant” comes close to “girl” in terms of frequency, neither come close to “give,” and “ginger” trails far behind. I think it’s also worth noting that the vowel of “give” reinforces [gɪ]. “Giant” doesn’t (but then again, neither does “girl”.)

One additional bit of evidence for [g] looking backwards, from the pronunciation of [gɪ] and [dʒɪ] towards letters (so, not just words containing the written letters “gi”). At the beginning of words, [gɪ] is spelled “gi” more often than not (e.g., “gui” or “gea”), while [dʒɪ] is more often spelled “ji” than “gi”. (Note that while I didn’t process this part of the data for related forms, there are few enough of them that you can eye them.)

Everything else: [dʒ]

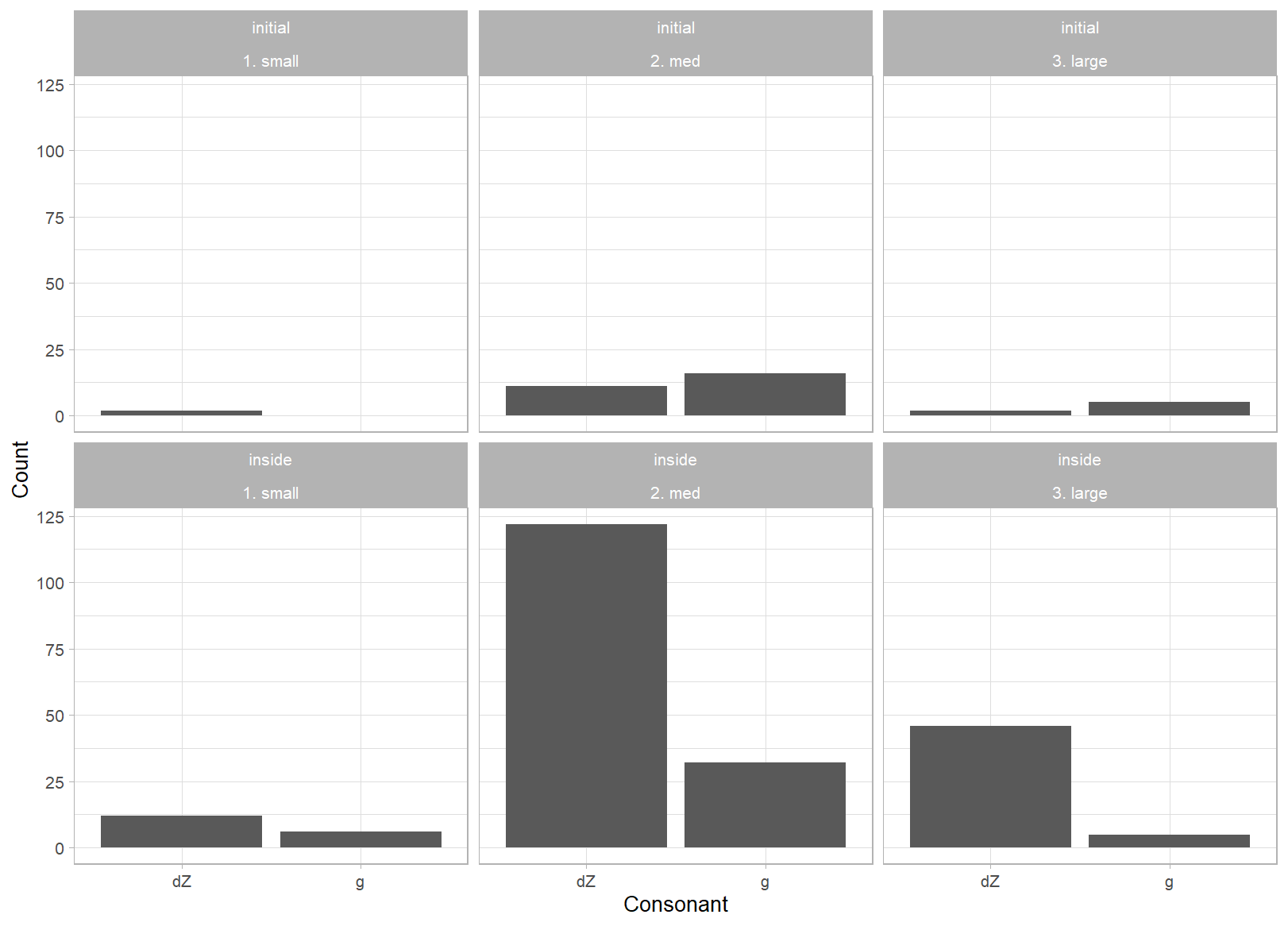

This might sting for you [gɪf]-ers. Outside of word-initial position, everything’s flipped. [dʒ] forms are more numerous (180, vs. 43 for [g]) and common (average log frequency: 6.06, vs. 5.2 for [g]). Even if you categorize words into “bins” of frequency (small, medium, large), the trend is the same: [dʒ] has more forms, by far. (The effect is most pronounced in words with middling frequency.) You can see this in the graph below. Word-initial “gi” forms are included as a point of comparison.

While it’s harder to gauge the correspondence working backwards, the fact that the letter “j” is more frequent at the beginning of words than inside words should be an indication that internal [dʒɪ] maps fairly frequently to “gi”. (Of the 230 unprocessed forms containing internal [dʒɪ], only 9 had the letter “j” anywhere in their written forms. Only 23 were missing the “gi” letter sequence.)

Finally, remember those forms I cut out? All the “arranging”, the “-ologies” and so on? Their regularity and productivity (you can turn anything into an “-ology”) keep piling on extra “gi” ↔ [dʒɪ] correspondence inside words.

What does this mean?

Let’s step back for a moment and ask: what’s “right” and “wrong” when it comes to stakes like these, the pronunciation of a word? Is it what an authority said (for those of you who invoke Steve Wilhite)? Tempting as that might be, I advance (and I think most, if not all linguists would agree with me) that “right” is simply an intelligible form implicitly understood by a speech community. That is, it’s right because they agree it’s right. There may be “right within our community” vs. “right in some other community that I can gauge” (like dialectal differences), but there’s also “wrong” in the sense of “I don’t know anyone who says it that way.” Dare I say, for instance, that we native English speakers are all in agreement that the “i” in “gif” doesn’t make the vowel [i] as in “beach.” The evidence is just that strong and consistent in English that the letter “i” makes the sound [ɪ] when it’s in a syllable that ends with a consonant (or at least a consonant like [f]). Change the spelling to “geaf,” and our intuitions change.

Bottom line is, hard as it is to accept, language actually is a democracy. That’s Linguistics 101, when we talk about the arbitrariness of capital-L Language. And between the [dʒɪf]-ers and [gɪf]-ers, really all we differ in is what generalizations we made from our vocabularies, in order to decide how the word “sounds to us.” Some of us pay attention to word position, others to trends in the lexicon as a whole. The rest is just after-the-fact attempts to justify ourselves and have some fun along the way.

PS

…all that said, it’s [dʒɪf]. #sorrynotsorry